- Serica Initiative

- Aug 15, 2025

- 4 min read

In 2016, Michael Luo was standing with a group of friends and family, all Asian-American, on the sidewalk in Manhattan’s Upper East Side neighborhood. A woman brushed past him, aggravated that they were in the way, and yelled “Go back to China…go back to your f—ing country!”

“I was born in this country!” Michael responded. But that didn’t change the fact that for many, including that woman and Chinese-Americans themselves, there has always been a feeling of exclusion and isolation for the Chinese in America. In return, Luo wrote Strangers in the Land, not just a history of the Chinese in America, but a collection of vignettes that illuminate how the Chinese fought to resist the sentiment that they did not belong—that they were “strangers in the land.”

“It’s almost like a who’s who of horrible stuff that happened to Chinese people." —Ronny Chieng, The Daily Show

Though Luo’s novel chronicles the extended and intense struggles of the Chinese in America, including one of the largest mass lynchings in US history against Chinese immigrants in 1871, it also enriches this history with stories of a resilient community, led by individuals and changemakers whose efforts were often lost in the mist.

“History is written by the powerful. And the powerless are often left out of history.” —Michael Luo, The Daily Show

Huiguans, Chinese mutual aid associations that represented new immigrant members in arrival, labor, and life

Some of the earliest accounts of Chinese-American history come from reports of huiguans, which represented the interests of new immigrants to the country and often formed based on the regional origin of their members. The first two chapters of Strangers in the Land tell the story of Tong Achick, a young Chinese merchant whose early education and fluency in English enabled him to lead the Yeong Wo Association huiguan, serving as a translator and advocate for Chinese miners who were abused and deprived of justice. Though the Chinese continued to face “near-constant strife”, Tong Achick, along with other early huiguan leaders like Norman Assing and Yu Wa, continued to advocate for the rights of the Chinese, serving as interpreters in court, negotiating taxes with the government for better treatment of Chinese miners, and offering cash rewards for information about their murdered community members.

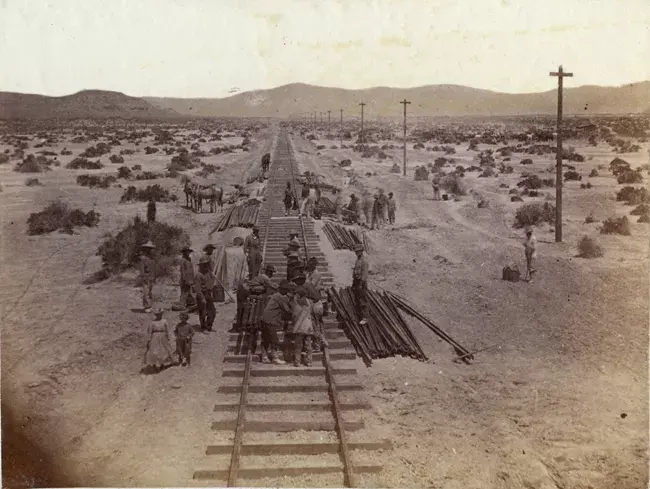

Hung Wah, a Chinese foreman crucial to the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad

As Chinese workers continued to be violently barred from mining, Hung Wah, a labor contractor, was able to recruit a large number of Chinese laborers to work on the Central Pacific Railroad. Construction on the railroad was daunting in terrain, intensity, and danger, but by July 1866, Hung Wah was supplying over nine hundred men to work on the railroad, allowing for an unprecedented speed of construction—half a mile of track laid in less than twenty-eight minutes. At the momentous completion of the transcontinental railroad, Luo captures the celebration of James Strobridge, the construction foreman of the Central Pacific Railroad, and a group of press and infantry officers, alongside Hung Wah and his team of laborers—“the assembled guests gave the Chinese three rousing cheers.” However, like many other Chinese leaders, Luo found that Hung Wah’s accomplishments were often faded in history, as his obituaries remembered him as a “town eccentric”, and failed to recognize his instrumental leadership on the Central Pacific Railroad.

“[There are] parallels in our story and that of other immigrant groups in this country…Asian-Americans benefited from the Civil Rights Movement and the rights that were fought for and bled for." —Michael Luo, The Daily Show

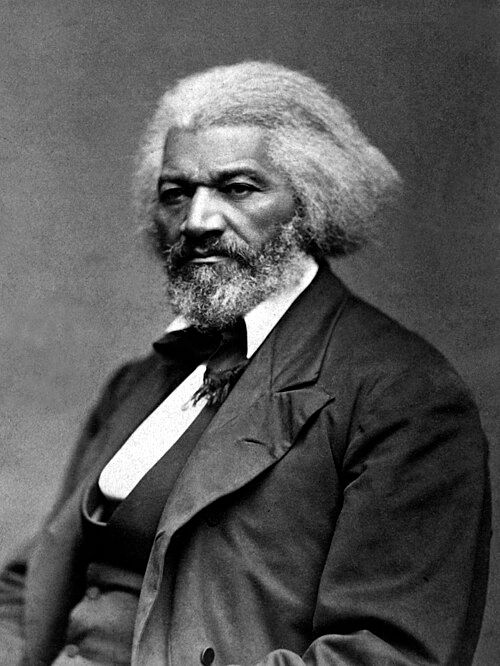

Frederick Douglass, a Civil Rights Leader who urged Americans to embrace the Chinese in a new composite nation

For many early Chinese leaders, their efforts were supported by Americans who took an interest in Chinese education, labor, and citizenship. As many immigrant groups poured into a post-Civil War United States, the Chinese struggled alongside other minority groups also hoping to belong in a new world. Frederick Douglass, a prominent leader for the abolition of slavery and African-American civil rights, continued to advocate for the wave of Chinese immigrants entering the country. In his 1867 speech, “Composite Nation”, he asks “Do you ask, if I favor such immigrations? I answer I would. Would you admit them as witnesses in our courts of law? I would. Would you have them naturalized, and have them invested with all the rights of American citizenship? I would.” A few years later, citizenship for the Chinese population was up for debate in the Senate. Though anti-Chinese sentiment persisted and prevented Chinese immigrants from becoming naturalized citizens in 1870, the “Chinese question” had been raised, yet to be answered.

“I think it’s so important to say their names so we can know who they are and tell their stories." —Michael Luo, The Daily Show

For Luo, Strangers in the Land is not just the story of Chinese-Americans, but also the story of “any number of immigrant groups who have been treated as strangers.” Though Asian-Americans are the fastest growing ethnic group in America, their history is often rendered invisible and their status as Americans rendered alien. Luo tells the stories of these “strangers”, giving names to the lives that struggled and succeeded to carve out a sense of belonging in their new land.

To learn more about Strangers in the Land, join The China Institute and The Serica Initiative in conversation with Michael Luo on September 24, 2025. The event will be held at the China Institute in America and broadcast live on the China Institute Youtube channel. See you there!